NIH: Reinventing the wheel is immoral

Every modern software service or product is comprised of several different moving parts, from simple tooling to runtimes, frameworks, libraries, messaging systems, data stores, web servers, load balancers, caches and much more. Companies hire us, software engineers, to put that puzzle together and help them fulfill their business goals, which usually include making or saving money.

Oftentimes part of our job is to decide (or influence the decision) on whether to build a given component in-house, or use an existing opensource / proprietary solution off the shelf. Each choice comes with its own cost and risk, and the answer is not always straightforward, but ultimately we are responsible for providing an educated and fully-informed input.

In many cases, such a decision might affect the system’s overall cost, quality, security, timeline, required talent etc. Needless to say that it cannot be taken lightly.

Unfortunately, the industry is plagued by a cognitive bias called the Not Invented Here syndrome (NIH), which drives us towards rejecting all possible existing solutions by default, in favor of implementing a new one from scratch.

Standing upon the shoulders of giants

Today we have many spectacular solutions at our disposal. We are able to perform extremely hard tasks with ease, due to decades of hard work and pioneering by our predecessors.

In any given software stack, all common and recurring problems have already been solved. The solutions come in many forms, such as high-level language features, functions within a platform’s standard client library, or third-party components.

When consuming an external system there is usually an accompanying client library to help us. When working on the cloud there are myriads of services and features we can snap together and formulate elegant solutions.

That’s really extraordinary. It means that we can avoid tons of expensive technical work that others have already done for us, as it generally doesn’t make sense to waste resources coding things we can buy or get ready-made.

Instead, we can focus on spending our time doing what we were hired for in the first place, and that is delivering value by coding our business rules into working software.

If we were building a new house we would buy ready-made cabinets, doors, windows, kitchen counters, ovens, refrigerators, dishwashers etc. Unless we were some kind of mechanical/woodworking geniuses, we wouldn’t consider building them ourselves.

When building software systems we are supposed to do the same thing. It makes no sense to write our own mechanisms for things like logging, caching, dependency injection, user authentication / authorization, XML/JSON serialization, load balancing, analytics, web apis, and many many more.

Yet so many of us fall into the NIH trap, often causing irreversible damage to our system and business. What kind of thinking could lead us into such a mess? Let’s examine some common preconceptions.

Preconception 1: In-house implementations are faster to develop

We tend to believe that writing our own code is faster than learning how to use someone else’s. And because we’re always too busy, we feel that we don’t have enough time to properly evaluate existing solutions.

When we do evaluate an existing solution, the process is often superficial and biased. We only spend a few moments brushing over the basics just to quickly reject them as inelegant, complex or unsuitable. The idea of a shiny new implementation quickly takes over, and a proverbial hand starts patting us on the back for the great work we’re about to do.

In reality, in-house implementations feel like they are quicker to develop, but the only fast part is coming up with a rough idea of what needs to be done. Dealing with detailed planning, execution, quality assurance and maintenance phases, though, is a whole different story.

Any solution should come at minimum with a good suite of automated tests and sufficient documentation. Skipping any of that in hope to go faster is a recipe for disaster, as such speed benefits are only short-term, and the technical debt we create of ourselves slows us down significantly just a few steps later.

Speed-wise, we should also be thinking about how good our team is with estimations. Do we miss our targets a bit too often? Do we spend most of our time fixing bugs, while core business behaviors are stuck in the backlog? If any of that is true, it’s probably not a good idea to put more work our way, especially if we can avoid it by using an existing implementation.

Preconception 2: In-house implementations are cheaper

What if using an existing solution comes with a paid license or support plan? Wouldn’t then be cheaper to build rather than buy?

A commercial license is typically priced at a small fracture of the total design, implementation and maintenance costs of a given software solution. We could argue that we are only interested in a subset of the features available in that solution, and if we were to build them ourselves we wouldn’t have to productionalize them independently. Although valid, these points don’t prove which choice is cheaper.

The most underestimated costs are those of maintenance. As mentioned previously, oftentimes we end up with half-baked solutions in favor of short-term speed. These prove to be very expensive to maintain, extend, or onboard people with.

The moment such an implementation leaves our hands it becomes legacy, and the next time somebody in the team or organization needs something similar, usually ends up with yet another custom one. That cost quite high, without even considering the implications of a defect ending up in production.

Let’s not forget opensource. For every standard component of a software system there are typically multiple opensource offerings we can take advantage of, and most of them can be used for free. Most importantly, we have the option to look at their source code, contribute, or even fork them and drive them towards a different direction if needed.

Many opensource solutions come with optional support plans. Through these, we can get direct answer to specific questions, recommendations, and first class support when a problem occurs. That is also usually cheaper than having to develop, document, test and maintain the code ourselves.

Even better, the larger the community is behind an opensource project, the easier it is to find answers to our questions fast and for free, eg. through Stack Overflow.

Although obvious, it needs to be mentioned that development time is quite expensive, which means that custom solutions that are slower to develop (properly) are also more expensive.

Preconception 3: In-house implementations are more secure

Security is a huge concern for software systems. Especially when exposing a service over the internet, we need to make sure that we do everything we can to protect our customers and organization. Some think that third-party implementations are by definition less secure than in-house ones. That’s a big misconception.

We tend to think of in-house solutions as more secure mostly because the implementation details are hidden from public eyes, therefore any potential flaws won’t be directly visible to attackers. In Security Engineering this point of view is called security through obscurity, and has been rejected by security experts as far back as 1851.

Popular third-party implementations have been battle-tested again and again, in numerous different scenarios. Especially in opensource solutions, there many more people examining the source code and spotting possible vulnerabilities compared to in-house implementations.

The main point is, we should never assume that our implementations are more secure than alternatives just because they are developed in-house. That is, unless security experts are involved and security audits are performed on a regular basis.

Preconception 4: In-house implementations are more innovative

Let’s just rip off the band-aid:

Outside innovation is always bigger than Inside innovation

Unfortunately, there are many organizations claiming to be innovative without having a clue what that word really means. Most of these cases refer to in-house implementations that don’t solve any new problems, but someone somehow somewhere convinced their boss or team that it’s a good idea to reinvent the wheel.

And because those implementations are usually not that important for fulfilling the main mission of an organization, the resources allocated to them are much less than what’s actually needed. We’ve already discussed the consequences of half-baked implementations in previous sections.

Innovation boils down to having a community around you and not solving everything by yourself. It’s like a spoken language; the more the people who speak it, the stronger it is.

That’s why many top organizations in the industry have opensourced large parts of their stack. They don’t just help the community, but also themselves by tapping to the collective effort of numerous other organizations and individuals.

Most importantly, innovation bears the weight of proof. Academics have been practicing the scientific method since the 17th century, and it’s not a coincidence that most breakthroughs in both Computer Science and Software Engineering have been guided by academic research.

Truly innovative organizations follow the same steps, publishing scientific papers (or funding scientific researches), getting peer reviews, accepting external contributions and proving their hypotheses in a formal and structured way.

Preconception 5: In-house implementations are better aligned to business needs

Although it sounds reasonable, this preconception is easy to misunderstand.

A typical software system is composed of several components, arranged within many different layers of abstraction. At the heart we can find the use cases, the whole purpose for the system’s existence.

All other components are secondary and revolve around the use cases. Components like databases, frameworks, messaging systems, web frameworks - even the web itself - are implementation details.

You can read more about software architecture in Robert C. Martin’s excellent latest book, Clean Architecture: A Craftsman’s Guide to Software Structure and Design (Amazon affiliate link)

Under most circumstances, building such components from scratch is a waste of resources, and it’s much more preferable to use commercial or opensource third-party implementations instead. That way it becomes a matter of customizing and composing those components together to formulate our unique system.

We should only build a component in-house if it’s unique to what we do and can be considered as a strategic asset. We should buy or use opensource if our use of the component is not that special.

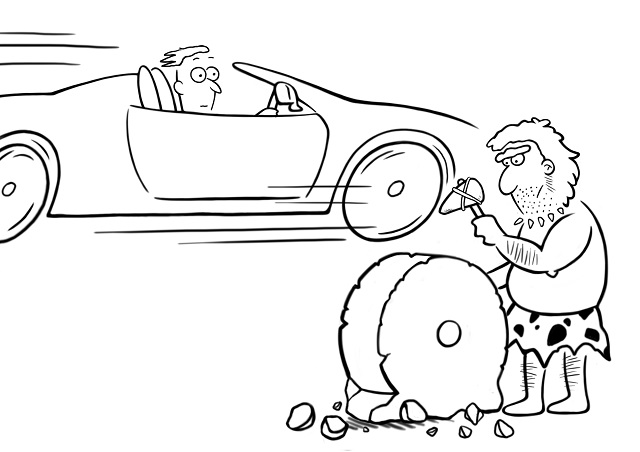

Reinventing the wheel is immoral

In a previous story we discussed that as engineers we are also stakeholders of the systems we work on, which means that we bear much responsibility for ensuring their long-term success and prosperity.

As we discussed, there are many common preconceptions about in-house implementations. We need to make sure that we are fully aware of them before affecting any relevant decisions in our team or organization.

Reinventing the wheel is not just a waste of resources. It also diverts our focus from implementing business use cases to dealing with development and operations work we could have avoided in the first place. That gives our competitors an advantage, as we move slower and face more problems than them. Self-sabotaging our systems in such a way is highly immoral.

Image source: aic.cuhk.edu.hk

The worst form of the Not Invented Here syndrome is doing projects just for the sake of enriching our CV. This is also called CV-Driven Development.

Every software engineer has to, at least once, implement a compiler, a cache, a view engine, and various other common components from scratch, for training purposes. These exercises should only take place during personal time and should definitely not be put into production.

Left unchecked, the NIH syndrome can turn a codebase into a graveyard of ambitious half-baked projects. Although it’s always easier to learn on someone else’s dollar, it’s also highly immoral.

Become a DrinkBird Insider

Never miss a post! Get the latest articles on tech and leadership delivered to your inbox. Sign Me Up Sent sparingly. Your privacy is a priority. Opt-out anytime.

Recommended Books

Full disclosure: the following are Amazon affiliate links. Using these links to buy books won't cost you more, but it will help me purchase more books. Thank you for your support!