Your org chart might be your biggest architectural constraint

It always starts quietly enough. One team takes on the customer portal, another handles authentication, and somewhere a platform group builds tools that nobody explicitly requested, but everyone will eventually need. As time passes, these boundaries between teams harden and become visible seams in the system itself. Communication flows smoothly within each unit, but it slows and sometimes stalls at the edges. The evidence appears in duplicated integrations, mismatched naming, critical paths that wind through multiple teams, and a growing backlog of cross-team handoffs that never seems to shrink.

This is not the result of poor planning or a lack of engineering skill. Even when teams are working in good faith, the architecture inevitably reflects the ways the organization communicates. Interfaces form exactly where conversations stop. In my previous article, I introduced Organizational Behavior, the study of how human factors shape technical outcomes. Here, I continue that exploration by examining why your system architecture so often ends up as a mirror of your org chart.

This is a sociological problem far more than a technical one.

How communication becomes architecture

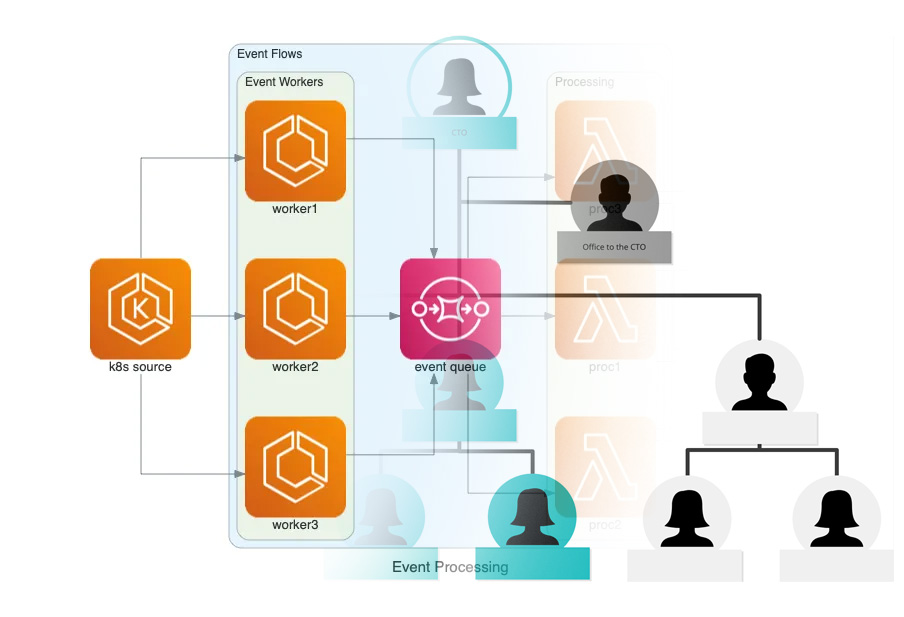

In 1967, Melvin Conway introduced a simple but powerful observation: organizations design systems that reflect their internal communication patterns. Conway’s Law suggests that the structure of your team shapes the architecture you build, sometimes more than any technical rationale. When groups struggle to collaborate, the software they produce tends to have awkward integrations and distinct boundaries that echo those org divides.

Technical solutions always depend on human interactions. Teams that work closely together tend to build unified solutions, while teams that rarely communicate end up producing fragmented systems. Conway’s Law explains why software interfaces so often map directly to team divisions instead of to logical technical boundaries.

This happens because organizational structures including communication pathways, reporting lines, incentive systems and decision-making authority shape how teams interact. These are core topics in Organizational Behavior. The ways people coordinate, set priorities and interpret goals have a direct influence on what gets built and how it behaves under pressure.

You have seen Conway’s Law at work if you’ve ever encountered systems littered with mismatched concepts or duplicate tools that all seem to do the same job.

How silos form

Silos rarely appear by design. They emerge naturally when teams optimize for their own objectives, often without considering broader alignment. Within teams, communication is straightforward, priorities are clear and incentives are aligned. Once you move across teams, these connections weaken. Communication becomes less frequent, alignment is harder to achieve and mutual incentives are difficult to identify. Over time, these factors create silos, separated groups that operate independently, sometimes unaware of overlapping or conflicting work.

Incentives play a significant role in this process. When teams are measured only by their own productivity or feature output, collaboration quickly becomes a secondary concern. There is little reward for integrating smoothly with others or investing in shared solutions. This leads directly to duplicated efforts and neglected integrations.

This pattern appears consistently across the industry. Infrastructure teams often push responsibilities down to the application layer to avoid owning complex integration logic, while application teams rebuild components rather than coordinate with other application teams that might already own similar functionality. The immediate efficiency gain from avoiding coordination conversations comes at the cost of system complexity and operational overhead later.

Role ambiguity makes things worse. Teams that focus on avoiding concrete ownership responsibilities in favor of broad mandates often leave critical tasks unclaimed. The resulting architecture reflects these organizational boundaries perfectly, with scattered ownership, inconsistent behavior, and unclear accountability when integration issues arise.

Even well-intentioned leadership efforts to clarify ownership can backfire. In many organizations, when leadership mandates explicit ownership for every component, teams frequently write rosters that conveniently exclude less attractive pieces. When pressed to take responsibility for orphaned systems, teams deflect by claiming these components fall outside their intended scope. This results in organized responsibility avoidance, where mission statements become shields against unsexy but essential work. This pattern has been documented extensively in industry literature.

Autonomy without alignment creates chaos

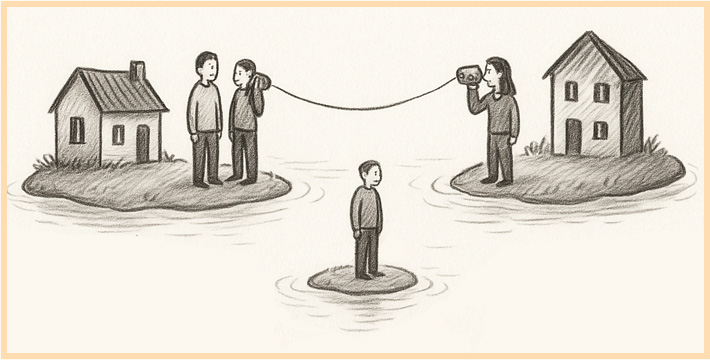

Autonomous teams have an obvious appeal. Each group chooses its own methods and moves swiftly without external bottlenecks. But autonomy without alignment quickly turns into chaos. When every team picks different technologies, conventions or processes, systems fragment into isolated islands. The efficiency gained by individual autonomy is quickly lost in cross-team friction.

This fragmentation isn’t a failure of autonomy itself but rather a misunderstanding of it. True autonomy doesn’t mean total independence. It requires a shared vision that defines clear boundaries and common interfaces. Leadership’s role becomes essential here, not in dictating individual team actions but in consistently reinforcing a unified architectural vision.

Reversing Conway’s Law

If Conway’s Law describes a natural tendency, then intentionally reversing it becomes a strategic move. This is sometimes called the Reverse Conway Maneuver, a term popularized by software architects who realized that you can shape your system architecture by first shaping your teams.

Leaders can influence outcomes by explicitly incentivizing collaboration, reorganizing teams, adjusting reporting lines and building a strong shared vision. In this way, the organization is structured to address immediate demands while creating the foundation for the systems it aspires to build.

The popular approach known as Team Topologies provides practical guidance for this kind of change. It recommends organizing teams around clearly defined business or technical domains and establishing thoughtful interaction modes. For example, instead of having separate frontend, backend and QA teams that must coordinate for every feature, you might have a stream-aligned team that owns the entire customer checkout experience, working alongside a platform team that provides shared authentication services. When teams are aligned with logical value streams rather than traditional functions, the system architecture often follows suit.

Restructuring alone is not enough, however. Culture and incentives must shift at the same time. When integration, collaboration and proactive communication across team boundaries are recognized and rewarded, the Reverse Conway Maneuver becomes more than a one-time experiment and can lead to lasting architectural improvement.

Practical steps to align teams and systems

Begin by auditing your current organizational and architectural structures. Identify the friction points where system seams match team boundaries. These intersections are where improved communication or structural changes can have the greatest impact.

Make ownership explicit, especially in areas that have historically been neglected. Who is responsible for documentation, integrations, shared infrastructure and cross-cutting concerns? Assigning clear responsibility prevents critical tasks from slipping through the cracks.

Encourage and reward collaboration directly. Adjust incentives so that teams benefit from collective success, not just individual output. Regularly reinforce the architectural vision and revisit structures frequently to ensure alignment remains strong.

Conclusion

The shape of your system reflects the habits and choices of the people building it. If you want to influence your architecture, start by focusing on how your teams communicate, set priorities and work together. Conway’s Law serves as a reminder that Organizational Behavior and technical outcomes are deeply linked. Understanding this connection gives you real leverage for change.

If you have faced similar challenges such as distributed ownership, fragmented systems or team-level misalignment, I’d be interested to hear how you’ve approached them.

In the next article, I’ll focus on another foundational topic of Organizational Behavior, psychological safety. It plays a central role in how teams collaborate under pressure, make decisions and take ownership of outcomes that shape your architecture.

Best, Tasos

Become a DrinkBird Insider

Never miss a post! Get the latest articles on tech and leadership delivered to your inbox. Sign Me Up Sent sparingly. Your privacy is a priority. Opt-out anytime.

Recommended Books

Full disclosure: the following are Amazon affiliate links. Using these links to buy books won't cost you more, but it will help me purchase more books. Thank you for your support!