A strategic approach for applying software design patterns

The problem with design patterns

One of the most important elements of software engineering is design patterns. These proven solutions to common development problems are truly invaluable assets. They help us create cleaner, more robust and less error-prone software, to name a few of their benefits.

Yet, experience shows that patterns may also lead to less preferable solutions, or even introduce more problems and technical debt than originally. In addition, some engineers believe that patterns may look ideal in book examples, but they do not actually work well in real-world solutions. These opinions usually stem from negative personal experiences. The question is, how is this possible?

A common mistake

There are strategic decisions to be made when applying a pattern in a solution, mostly related to the separation and implementation of class concerns. These decisions can make or break a design. Apart from choosing the right pattern for the right reason, timing is also a very important factor.

Many designs fail because a pattern is applied too early in the process, before the design is ready to accept it and incorporate it as its natural extension. In such situations, the requirements are bent to conform to an expected pattern. The design might seem admirable to begin with, but soon starts to illustrate various defects. At the end, the pattern is usually blamed, but the true origin of the problem is totally overlooked.

The evolutionary way

Every successful software design progresses in small and focused phases. Our purpose is to understand the design and deliberately guide that progression. Instead of blindly inject a pattern that looks suitable, we should let the pattern grow out of the design. That way we also make room for the pattern’s implementation to progress smoothly along with the rest of the design.

Patterns are not code formulas. They provide an outline of some segment of a solution, but the implementation details vastly differ from one solution to another. Thus, there is no surprise that applying the same pattern the evolutionary way, in contrast with applying it too early in the process, results in significantly different implementations.

The details are not the details, they make the design – Charles Eames

Neuropsychology to the rescue

Asking the right questions is essential for keeping us on track. We always need to provide a clear answer on why we need to apply a specific pattern, what is the benefit we are pursuing, how we are planning to implement the pattern in the specific programming language we are using, and most importantly, when is the proper time to take action.

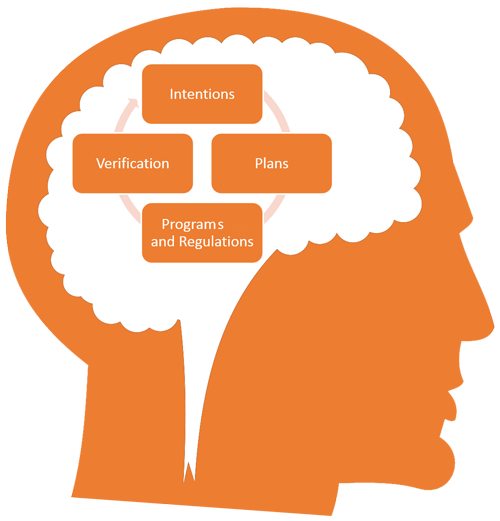

The last question is probably the trickiest to answer, because conditions leading to the application of a pattern are usually not quite apparent. That’s when studying the brain can be more than revealing. In his book The Working Brain, Aleksandr R. Luria, a famous neuropsychologist and developmental psychologist, presents an intriguing view on how humans solve problems:

“Man not only reacts passively to incoming information, but creates intentions, forms plans and programmes of his actions, inspects their performance, and regulates his behavior so that it conforms to these plans and programmes; finally, he verifies his conscious activity, comparing the effects of his actions with the original intentions and correcting any mistakes he has made.” – Aleksandr R. Luria

This sentence describes lots of common elements with what we actually do in software design cycles.

- Intentions: At first we gather requirements for a new system or feature. This is usually a passive task, where we collect as much information as possible to help us prepare for the problem solving activity.

- Plans: Beyond this point our intentions become final, at least for the current iteration. Based on the requirements, we formulate an analysis to define and describe the exact sequence of activities to follow.

- Programs and Regulations: Next we apply our technical knowledge in order to produce an actual implementation. During this process we always make sure that we follow the plan.

- Verification: Finally the implementation is evaluated, usually in the form of acceptance testing. We need to make sure that the implementation conforms to the original requirements. In case we detect any deviations or deficiencies, the whole process needs to be repeated. The new design iteration should begin by using these problems as input.

How do patterns relate to that process?

In simple terms, it is crucial not to involve any patterns during the first iteration. Applying a pattern too soon usually leads to a serious compromise; we have to bend the requirements in order to accommodate for that pattern, so the problem is put into a mold and parts of the problem definition are left outside. Soon we realize that more iterations are needed in order to patch the design up, so technical debt prevails and productivity is plummeted.

While design patterns catalog books deal with generic examples, real-world implementations are always unique and tailored to a specific problem. We don’t want this implementation to be negatively affected by other implementations.

However, it is never too late to refactor the design and apply a pattern later in the process. When a working implementation is already available, we are able to examine it thoroughly and apply patterns as solutions to specific local problems. This is exactly where patterns fit the best.

Of course, we need to have a strong technical background in software design patterns beforehand. Catalog books such as Design patterns : elements of reusable object-oriented software are still the strongest weapon in our arsenal for achieving that.

Conclusion

Many software solutions fail due to accumulated technical debt, which often stems from the premature application of software design patterns. Apart from having a strong technical background in patterns, we need to understand that knowing when to act is equally important to knowing when not to.

Become a DrinkBird Insider

Never miss a post! Get the latest articles on tech and leadership delivered to your inbox. Sign Me Up Sent sparingly. Your privacy is a priority. Opt-out anytime.

Recommended Books

Full disclosure: the following are Amazon affiliate links. Using these links to buy books won't cost you more, but it will help me purchase more books. Thank you for your support!