![[Book Review] The Lean Startup by Eric Ries feature image](/images/the-lean-startup-eric-ries.png)

[Book Review] The Lean Startup by Eric Ries

##Introduction There is incredible failure that precedes every entrepreneurial success. Even the most promising idea can be doomed from day one if the entrepreneur is not familiar with a suitable process needed to turn that idea into a successful company.

Eric Ries is a talented author, blogger, and Silicon Valley entrepreneur. In his early career he consistently worked hard on products that ultimately failed in the marketplace. He initially treated these failures as technical problems that required technical solutions, most likely due to his background as a computer scientist (Businessweek, 2014). Surprisingly, this approach was yet another mistake.

Being hungry for new ideas and approaches, Ries started studying about other industries until he stumbled upon the lean manufacturing, a process that reimagined the manufacturing of physical goods. Taking ideas from lean manufacturing and properly adapting them to entrepreneurship, he envisioned a ground-breaking business strategy called The Lean Startup, which he describes thoroughly, along with detailed evidence of its effectiveness, in his homonymous book.

In his work, Ries argues that although as a society we have mastered both the management of big companies and the best practices for building physical products, when it comes to innovation and startups we are still failing miserably. Countless startups begin with a conception of a product that they think people want, then spend long periods of time perfecting that product without ever showing it to any impending customers, even in a preliminary form. When they fail to meet the market’s expectations, it is usually because they never involved those customers in the process of determining whether or not the product was actually going to be interesting or useful.

The Lean Startup lays out a scientific method for building a sustainable business and minimizing the time needed for a desired product to reach the customer’s hands. This method provides a solid foundation for driving a startup, understanding when to change course, when to persevere and ultimately learning how to achieve growth in the fastest pace possible, along with avoiding the waste of development talent, energy, and effort.

This book was found to be particularly interesting, even inspiring, as the author is engaged in continuous storytelling, offering an affluence of insights on how some real 21th century startups repeatedly overcame imminent failure and became success stories by applying the lean startup methodology. Every entrepreneur, manager, engineer or marketer should read this book because it can literally impact their lives for the better.

##Overview of Part One – Vision

Startup success can be engineered by following the process, which means it can be learned, which means it can be taught. – Eric Ries

A startup is described as a human institution designed to create a new product or service under conditions of extreme uncertainty. It is the word uncertainty which makes the lean startup approach so appealing to entrepreneurs as it tries to eliminate as much uncertainty as possible from the whole process. It is explained that entrepreneurship is a kind of management, a fact that most people still ignore.

The lean startup methodology was inspired from the revolutionary lean manufacturing technique that Taiichi Ohno and Shigeo Shingo are credited with envisioning at Toyota. Lean manufacturing completely changed the way supply chains and production systems run. Its basic principles include treating each worker as a creative being, shrinking batch sizes, achieving just-in-time production, achieving precise inventory control and accelerated cycle times. The main goal of lean thinking is the fast production of quality products with minimal waster. The lean startup adopts the core principles of lean manufacturing and puts it in the context of entrepreneurship. Rather than keeping entrepreneurs focused on producing high-quality goods, a concept called validated learning is helping them judge their progress in a vastly different way while figuring out the right thing to build in the fastest way possible. It is apparent that the right product is something that customers really want and are willing to pay for.

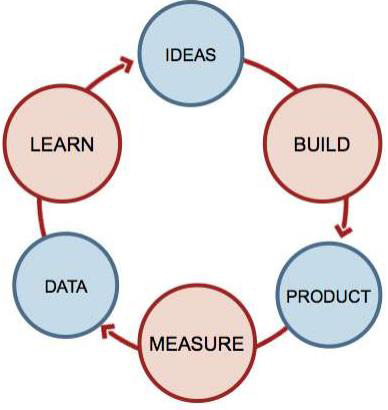

Instead of making complex plans based on assumptions, entrepreneurs are encouraged to create a minimum viable product and run a series of experiments on it to test their assumptions, revealing the behavior of customers in the process. A process called the Build-Measure-Learn loop is proposed as a guidance of the whole operation, offering insights in a timely fashion on whether the assumptions made are true or not, and making numerous changes to the product through the process of optimization. Less frequently, to protect their vision from failing to come true, entrepreneurs may consider a tight turn in the company’s strategy, called a pivot.

Product - Strategy - Vision

Through storytelling, the author describes the failure he experienced as a CTO in IMVU – an online 3D avatar startup – as his team worked six months for building something that nobody wanted. The company successfully achieved failure as the team could not adapt in time. Ries explains that this disaster could have been avoided if IMVU had tried to involve customers earlier in the process of product design. He also argues that a company’s sole sustainable path to a long-term economic growth is the creation of an innovation factory based on the lean startup principles, assisting in the creation of disruptive innovations on a consecutive base. The ultimate goal is to help teams progressing and innovating in sync with the experimentation procedure.

Learning what customers want and how they behave is the most important target of a startup; everything else is waste. In order to discover the perfect compromise between the company’s vision and what customers would find acceptable, a process called validated learning can be employed, altering the way metrics are being taken into account. Validated learning helps companies ignoring the so called vanity metrics that can be proven fatal – especially for startups – and focusing on more substantial indications. Ries describes this concept as a rigorous method for demonstrating progress when one is entirely embedded in the soil of extreme uncertainty (Ries, 2014).

In modern economy almost anything can be built. The challenge is deciding whether it should be built, or if a sustainable business can be built around a set of products and services. Ries advices that each startup, regardless of its classification, should be treated as grand experiment, starting with a hypothesis which is assumed to be valid, and some clear predictions about what is expected. The results of this experiment, positive or negative, should be used as feedback for efficiently tuning the engine of growth.

Figuring out whether a customer is actually being benefitted by a product or service once using it – also called the value hypothesis – and testing through what medium new customers will identify a product or service – also called the growth hypothesis – are the two most vital component parts of a company’s grand vision. Instead of a managers just ordering products and engineers just accepting the orders, a more analytical approach is proposed by Ries. Answering four critical questions about an aspirant new product can help teams figure out whether they are on the right path or not:

- Do consumers acknowledge that they have the problem we are trying to provide a solution for?

- If a solution existed, would they pay for it?

- Would they chose to pay us or someone else?

- Are we actually able to develop a solution for that problem?

The first part of the book ends by providing two startup success stories, the Village Laundry Service which provides low cost laundry services in India, and the Consumer Federal Protection Bureau, a US government agency that used the lean startup approach to succeed, clearly demonstrating that this approach can actually be used in any type of organization.

##Overview of Part Two – Steer

In the second part of the book, the author focuses on the importance of the Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop, which is perceived as the heart of the lean approach, and can be of great value to startups in means of saving time and resources while developing a product and adapting their strategy around it.

Build - Measure - Learn

Each business plan is established using a series of assumptions that guide the company’s strategy. It is of great importance that the entrepreneur is focused on building an organization capable of validating these assumptions systematically and rigidly, without losing sight of the startup’s overall ambitions. As described earlier, the most important assumptions for a startup are the value hypothesis and the growth hypothesis, which tune the company’s engine of growth and speed up the iterative process of BML. Some of the assumptions are quite safe as they have been well-established from industry experience, however leap-of-faith assumptions contain high risk and can either reveal tremendous opportunities or destroy the company. According to the author, some entrepreneurs create analogies in an attempt to hide the true risk of their leap of faith from investors, partners or employees.

It is described that Toyota’s success is based on the principle of genchi gembutsu – Go and see for yourself – which means that every business action should be based on solid direct knowledge. Entrepreneurs are encouraged to get out of their chairs and go meet with potential customers in order to understand them and confirm that they actually have a considerable problem to solve. To achieve a better prioritization of decisions while creating their product, a company might craft a terse document that seeks to humanize the customer it aims to appeal, called the customer archetype.

In order to start the learning process as soon as possible, rather than falling in the pit of too much analysis or none at all, startups need to create a minimum viable product (MVP). This product has to be unburdened from any features that don’t contribute directly to the learning cause. After numerous iterations of the BML cycle, faulty parts of a company’s strategy can be identified resulting to a pivot. The story of Groupon, a leading company in coupon distribution, is discussed, as it started iterating by using a plain WordPress site, manual coupon creation and manual email distribution as an MVP. Groupon tested it hypothesis prior to investing in expensive, complex and automated software. MVPs are usually sold to early adopters at first, an unconventional type of customers willing to accept an imperfect solution for being the first to use or adopt it. As a result, they can help by providing valuable feedback and help forming the features that a product is missing.

It is argued that standard accounting is not helpful to a startup due to the conditions of high unpredictability the latter operates under. Innovation Accounting is an alternative approach geared specifically towards disruptive innovation. It transforms leap-of-faith assumptions into a perceptible financial model. It works by following a specific set of steps; Startups must use an MVP to establish real data on the current standing of the company. They must then attempt to move the idea away from the baseline and towards the optimal. After all product optimizations are made, the company has to make an important decision: pivot or persevere. MVPs are presented as initial learning milestones for a company, putting the company’s vision to constant testing. A pivot is considered successful if newer experiments are generally more productive than older ones, as long as the evaluation is not based on vanity metrics. Credible metrics are those who can be characterized as actionable, accessible and auditable. The author emphasizes the importance of split testing, a practice used to eliminate work that makes no difference in customer behavior, thus considered as waste. It also helps teams clarify what customers really want.

Next Ries wraps up the second part of the book by extensively analyzing the principles behind pivoting. All entrepreneurs must ask themselves whether they are making sufficient progress to believe that their original hypothesis is correct or either they need to take a step back and approach the issue from a different angle. It is important to pivot sooner rather than later before too much of the startups resources are being spent on something that will ultimately fail. This is why startups use Innovation Accounting, it helps lead to faster decisions on whether to pivot or not. The purpose of pivots is not described as a need to throw out everything that has been learned and start from scratch, rather than leverage knowledge harnessed from the previous data and repurpose it to move in a different, more efficient direction. Vanity metrics are again a major problem, because they can make entrepreneurs reach false conclusions therefore ignoring a potential imminent need for pivoting. Ten different kinds of pivots are described, each one engineered to tackle a different situation.

Overview of Part Three – Accelerate

The third and final part of the book is revolving around growth and maturity in a startup environment. Successful startups eventually grow enough to face big-company problems. The lean startup methodology is equipped with tools that allow startups grow without making discounts on speed or agility.

A lean startup’s advantage is the ability to work in short iteration cycles and in small batches. Working in small batches allows entrepreneurs to make faster observations and minimize the consumption of wasted resources. Ries describes a situation where a letter folding task proved to be faster by following the single piece flow, proving that a batch size of one is generally superior over large batches. In a large batch situation, for example, a possible failure of the letter to fit in the envelope would have been discovered nearly in the end of the process. Toyota decided to shrink the batch size of work instead of asking workers to produce faster. This decision led to a greater variety of products and to the creation of new value propositions. The need of storage also was dramatically reduced, and spare part distribution became rapid and inexpensive.

A technique called the andon chord was employed at Toyota within the context of lean manufacturing. According to this technique, the production line can be repeatedly interrupted throughout a day in order for identified problems to be fixed before the production of more batches occurs. As in lean manufacturing, lean startup entrepreneurs can leverage this technique to rapidly check for defects. Moreover, placing some automated defect checks, the possibility of breaking existing features during development is minimized, and the production line obtains its very own immune system.

In conjunction with the andon chord, the immune system allows multiple versions of a product to be shipped within a single day, allowing startups to get through the BML feedback loop faster than their competitors. The author refers to this concept as continuous deployment. In software industry some of the most common examples of continuous integration include hardware becoming software, fast production changes and 3d printing and rapid prototyping tools. It is noted that the BML feedback loop in reality works in the reverse order; after figuring out what they need to learn about, entrepreneurs work backwards to decide what product they can use as an experiment to achieve that goal.

The concept described next is the engine of growth, the method that lean startups employ to achieve sustainable growth. This method is based on a rule describing that fresh customers are the result of actions performed by existing customers, either by word of mouth, as a side effect of product usage, through frequent procurement or usage, or through paid advertising. The engines of growth are also described as feedback loops, designed to provide companies with a limited set of metrics to focus their effort on. There are different types of growth engines, and technically, multiple growth engines can operate in a company at the same time. Successful entrepreneurs chose one and try to make it work as efficiently as possible. The identified engines include the sticky, the viral and the paid engine of growth. A word of caution is provided for when an engine of growth runs out of gas; Companies need to perform a set of continuous and concurrent activities, trying to tune their engine of growth and at the same time trying to discover fresh sources of growth for when their current engine is exhausted.

An organization that easily adapts its process and performance to new conditions is described as an adaptive organization. Ries discovered firsthand that it is impossible to trade quality for time. Every quality problem, caused or ignored, is guaranteed to cause defects and slow the production process down in the future. Lean startups invest in slowing down the production to fix problems that waste time. This line of thinking is called adaptive processing. When a problem arises in a team, instead of the members blaming each other, Ries suggests that the most seniors should remember a simple phrase:

If a mistake happens, shame on us for making it so easy to make that mistake.

He introduces an impressive approach called the five whys, a way of forming five consecutively questions to identify and isolate the cause of any given problem. Anyone using the five whys is advised to be mentally prepared as it is guaranteed that negative facts about their organization will be revealed, especially at the beginning. Of course this approach only works in environments operating in good faith.

Ries also explains that the traditional waterfall methodology, which employs a linear large-batch production and tight deadlines and relies on planning and forecasting, is not a good fit for startups. He encourages a mixture of cross-functioning teams with no more than five members that also involve customers in the process of creating new products, processes and systems. Successfully put, a startup’s work is never done, because new sources of growth through disruptive innovation are constantly needed. Operational excellence is illustrated as an absolutely necessary part of the process.

The author once again focuses on the importance of disruptive innovation and the structural attributes required by startup teams operating within big companies. Those attributes include scarce but secure resources, autonomy to advance their business without being slowed down by red tape, and a personal involvement in the end result. The root organization has to make clear who the innovator is, and if a product is successful and is brought back to the root organization, the innovator should receive the proper credit.

As startups are extremely delicate to unexpected budget changes, their capital should be absolutely secure from tampering. Also very large budgets can be as harmful as very small ones, so a good balance is advised. As in terms of empowering innovation teams, a suggested course of action is to create an innovation sandbox which allows for more rapid experimentation with fewer risks, as any impacts on a product are only happening inside a controlled environment. Production speed is considered irrelevant as a strong emphasis is once again given in the speed of BML feedback loops. The faster a team can measure and learn, the faster it achieves success.

The book concludes by laying out some ideas about future approaches of the lean methodology and modern management in general. It also provides some important advice; Ries points out that the lean startup methodology should not be considered as a blueprint or as a set of predefined steps to follow. It should be perceived as a framework that can be adapted to the environment of each particular company. Every startup should be driven by genuine desire to discover the true facts behind its vision, and most importantly, should stop wasting people’s time.

Evaluation

This book was found to be particularly insightful. Using the narrative and storytelling techniques, Eric Ries achieves to capture the reader’s integral attention right from the start, by making clear that the stakes are a lot higher and a lot more interesting than just a book. Ries is an unconventional mixture of computer scientist, business practitioner and theorist who came to an understanding that even though as a society we are constantly devoting a growing percentage of our stamina creating new products, there are countless people involved in new projects knowing deep down in their heart that their daily labor does not matter to anybody. A massive amount of people’s energy, time and talent is being wasted. That unacceptable fact acted as a strong incentive for Ries to envision a disruptive world-wide movement that can change the way new products are being built and launched. Ries’s ultimate goal is to put the process of entrepreneurship and innovation to a more uncompromising and more scientific foundation.

A startup is described as a human organization dedicated to create new products and services under conditions of extreme uncertainty. The reader will welcome the proposed shift from regular general management to a new form called entrepreneurial management, which is based on a scientific method tailored for breaking through the wall of uncertainty and discovering a path to a sustainable business. After all, planning and forecasting can only work if a company has a long and stable operating history to extrapolate from. The fact that innovation can be managed scientifically implies that the recipe for success can actually be taught and learned. Moreover, the definition given to the word startup does not say anything about how big a company is, what industry it is working in, or what sector of the economy it is concerned about. The reason behind that deliberate description is that the lean startup principles can be applicable even inside big companies, government sectors or non-profit organizations. The book provides more than enough real-world examples from Ries’s personal experiences to back this theory up.

It is argued that time after time entrepreneurs are simply building the wrong things extremely efficient, so it is controversial to be proud for building something that nobody wants but in time and budget. A strong emphasis is given in the fact that customers do not actually know what they want; that human beings are psychologically unable to answer hypothetical questions about how they would behave at a later time. That is the reason why entrepreneurs are urged by the author to create a minimum viable product as soon as possible rather than procrastinate by overanalyzing specs and business plans, and then use that product as a subject of rapid experimentation to clarify whether their hypothesis or vision is true or not. In the reader’s mind, this procedure can be directly compared to a physicist that conducts experiments on atoms to reveal their behavior.

Amongst the highlights of the book was that the term learning is usually used in companies to justify failure. It seems that the existing system of accounting is essentially incapable of telling the difference between a team that spent some months learning really beneficial lessons and a team that spent the same amount of time doing nothing useful. On top of that, success measurement is often resorted in the evaluation of vanity metrics, which are the foundations of modern accounting. This presents a major problem, as the lean startup methodology suggests that the value in any entrepreneurial situation is learning whether we are on the path to a sustainable business; the rest is just waste. The methodology introduces the term innovation accounting along with a new unit of progress for startups, called validated learning that deal with the inefficiencies of conventional approaches. Along with a concept called the Build-Measure-Learn loop, it provides a powerful weapon to help entrepreneurs becoming more innovative, stop wasting people’s time and overall becoming more successful.

Another great point of the book that generated a lot of suspense through the real-world situations described, is the crucial subject of how and when a change in strategy is required in a startup. Ries unfolds the concepts of pivoting, a change in strategy without a change in vision, and persevering. It takes a lot of courage for entrepreneurs to admit that their strategy is based on the wrong facts, throw off a decent amount of work, and start experimenting again using a different hypothesis. Nevertheless, it is made clear that the goal of strategy in a startup is not to provide answers to entrepreneurs rather than help them figure out what are the questions they need to ask.

The lean startup methodology is consisted of multiple distinct concepts. The book follows an apparent logical flow with real-world examples that make each of the concepts stick to the reader’s mind in a natural and pleasing way. Since the book has been published in 2011, more companies each year align with Ries’s vision. A whole movement has been formed to support companies willing to adopt the lean startup methodology (Ries, 2014). The book is an exceptional piece of work and can literally transform one’s perception of entrepreneurship and management. Most importantly, it promotes the wise usage of the single most limited, valuable and irreplaceable resource that people have: time. Everyone involved in business should devote some time to read this book.

Conclusion

There is incredible failure that precedes every entrepreneurial success. Even the most promising idea can be doomed from day one if the entrepreneur is not familiar with a suitable process needed to turn that idea into a successful company.

Entrepreneurship is management, just not the classic management of Fred Taylor. Processes that we take so for granted today, like running a factory or a supply chain, had to be invented. All we know about entrepreneurship today is just the tip of the iceberg, and processes for operating under conditions of extreme uncertainty are still on the works. Eric Ries is renowned for pioneering the lean startup movement (Wikipedia, 2014), a movement that tries to discover those processes and helps startups using capital more efficiently without wasting it by building the wrong things. This book is a compelling evidence of this fact.

References

Businessweek, 2014. Businessweek. [Online] [Accessed 2-11-2014].

Ries, E., 2014. theleanstartup.com. [Online] [Accessed 3-11-2014].

Wikipedia, 2014. Wikipedia. [Online] [Accessed 2-11-2014].

Become a DrinkBird Insider

Never miss a post! Get the latest articles on tech and leadership delivered to your inbox. Sign Me Up Sent sparingly. Your privacy is a priority. Opt-out anytime.

Recommended Books

Full disclosure: the following are Amazon affiliate links. Using these links to buy books won't cost you more, but it will help me purchase more books. Thank you for your support!