Microservices communications: Publishing messages to a bus in a reliable way

The context

In microservices design, we often need a service to publish messages or events to a message bus to notify other services that something interesting has happened.

Perhaps a user has subscribed to our newsletter, and the Email Sender service needs to know so it can send a welcome email, or the Reservation Analytics service needs to be aware of all the reservations and cancellations within our restaurants’ platform to keep the business informed.

No matter which messaging solution we choose, e.g. Kafka, RabbitMQ, or Azure Service Bus, there is a common design problem that we need to be aware of and avoid.

The problem

Imagine that an interesting change is about to happen in our system; let’s say a user has filled out their information and is about to click the Register button. Upon processing this request, the User microservice needs to perform two actions:

- persist the new user’s information in its database, and

- publish a

UserRegisteredevent to a message broker

Both steps are essential for our system to function correctly, so they should either both succeed or fail. For example, if the user info gets persisted, but the event doesn’t get published, then the Subscription service won’t know about the new user and won’t activate their trial subscription.

It might sound essential that the two steps above are performed together, but this double write can lead to several problems. For example:

- When the message broker is down or unreachable: A message broker is an independent system with its own uptime/SLA, which means it can be down when we attempt to use it. We also communicate with it over the network, which is unreliable by definition, so the broker can be unreachable when we try to send a message.

- When the service is killed mid-way: As soon as the database persistence step completes, the service dies unexpectedly. The message publishing step doesn’t happen at all.

- When requests have to be processed fast: Talking to a database and a message broker means that we talk to two different systems over a network, which adds to the total response time. If our service’s response SLA is tight, this might be an issue.

- When we need to republish old events: Imagine that we have just deployed a new microservice, and it needs to catch up with all events that occurred within the last 30 days. The TTL (time to live) for messages in our bus is 7 days, so most of the events have disappeared. We need a way to republish these missing events without changing the state of any elements in the database. If those two actions are coupled, we have a problem.

Solutions

There are a few patterns we can leverage to avoid double writes. Which one to choose depends on the situation, as we need to consider some design aspects of our system, most importantly the database technology used by the service in question.

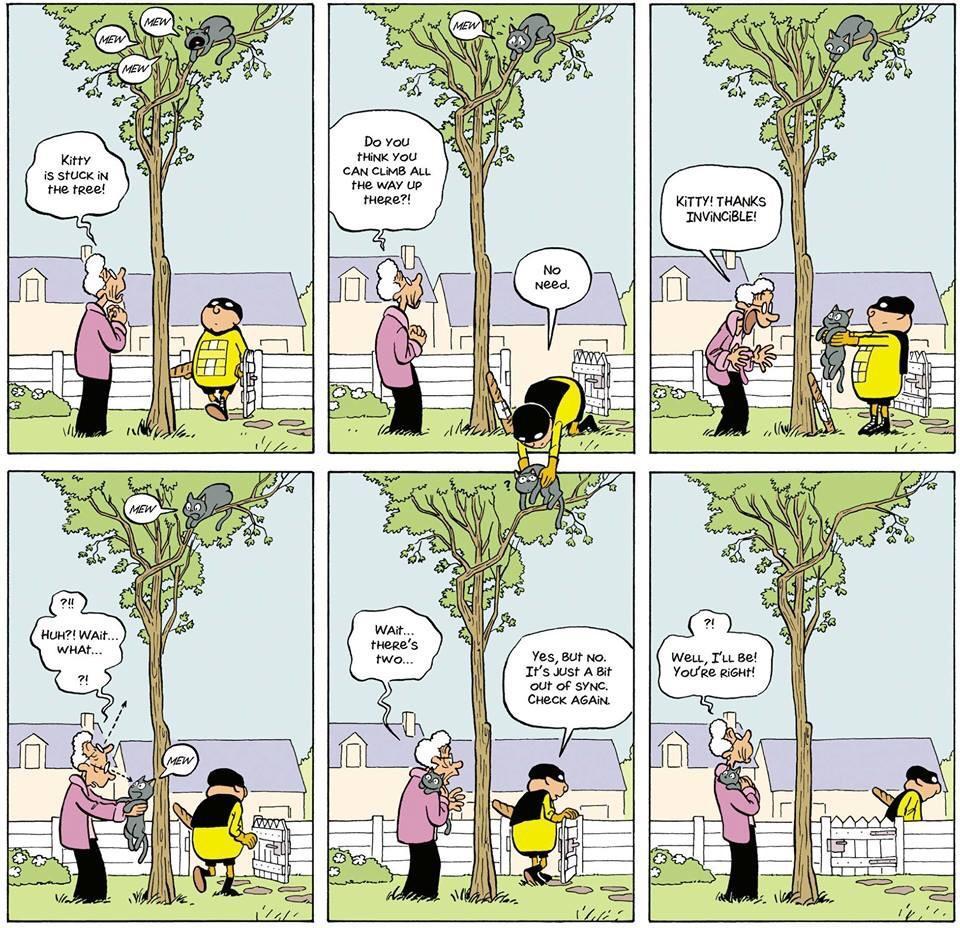

The premise of all the solutions presented here is embracing the eventual consistency model while atomically performing each required step.

That way, we can guarantee that services will get to know about the changes they are interested in, not at the exact time they happen but rather a few moments later (eventually). After all, sacrificing consistency in favour of high availability and partition tolerance is generally a good idea for cloud applications¹.

In addition, the service’s database becomes the source of truth for messages/events emitted to other consumers. That allows us not just to have better visibility into what and when something gets published but also be able to republish items if necessary.

Note that by using these patterns, the event consumers need to ensure idempotency, meaning that they should guarantee that they won’t process the same event more than once if the producing service publishes it multiple times on the bus.

¹ For more information on the subject, you can read about The CAP Theorem. Note that within a microservices-based application, not all components need to follow the same consistency model. For example, a Payments component could favour consistency over availability.

In Domain Driven Design terms, we only talk about eventual consistency between microservices / aggregate roots, not within the same one. An architect should be careful when designing subdomains to keep consistency levels inside one context and apply proper failure semantics across different domains. (Many thanks to Hrvoje Hudoletnjak for contributing this paragraph to the article.)

1. The Transactional Outbox Pattern

For applications that use a relational database to manage their state, we can use a special Outbox table as a staging area for messages to be published.

We use local ACID transactions to make changes to the application’s state, and as part of such a transaction, we also insert a message/event record into the Outbox table.

Then we can have a separate Relay process that reads messages from the Outbox table and publishes them to a message bus within a separate local ACID transaction.

It’s a highly convenient pattern, especially when we need an existing application to start publishing events. Most importantly, this pattern allows us to work directly with high-level events, in contrast with other ways we’ll see next.

On the other hand, additional programming work must be done when writing/reading outbox messages, so there’s always the chance that a developer forgets to update this part when making changes to the main application logic and data shape.

2. The Transactional Log Tailing Pattern

For applications that use a database which supports log tailing, we can have a Relay process that taps into the transaction logs, transforms detected changes into messages/events and publishes them to a message bus. Although this approach is similar to the Transactional Outbox, it has different pros and cons.

On the bright side, there is less development work involved as we don’t need to make any additional inserts when persisting state. On the other hand, the transaction logs are usually in a raw, lower-level format, and some work is involved in transforming them into high-level events.

This approach works for both relational and NoSQL databases, as long as they support the log tailing feature. A good example of a NoSQL implementation of this pattern is Microsoft Azure Cosmos DB with the Change Feed feature.

When working with Cosmos DB, the Relay service taps into the Change Feed API and receives notifications for data changes, which can then publish to a message bus. The Change Feed feature also works great with the full Event Sourcing pattern, which we’ll see next.

3. The Full Event Sourcing Pattern

With Event Sourcing, we persist the state of a business entity, such as a Reservation or a User, as a stream of state-changing events. To make a change to a business entity, we append a new event to the stream, and to recreate an entity’s state, we replay all events in the stream.

Since with Event Sourcing, we don’t edit records but only insert new ones; we always change state in an inherently atomic way. The challenge lies in publishing events to a bus in an atomic way as well.

When working with Event Sourcing, we refer to the database as the Event Store. Although there are products specialised in storing events, such as Greg Young’s Event Store, we can essentially use most SQL or NoSQL database products and adjust our custom event sourcing implementation to account for each database’s strengths and weaknesses.

The way we publish events reliably depends on the Event Store. For example, with a SQL implementation, we can have an Events table to store domain events and a flag that indicates whether a record has been published. It’s similar to the Outbox pattern, but we don’t need the additional Outbox entries.

Transactional Log Tailing is also a good option since, with Event Sourcing, it’s much easier to know exactly what to listen for and react to. Finally, the Change Feed feature fits naturally into the design when using Cosmos DB as an Event Store.

I have successfully used relational (Azure SQL) and NoSQL/document-oriented (Azure Cosmos DB) databases as an event store. The jury is still out regarding which approach is better, as there are cost, scalability and other factors to consider.

Nevertheless, you need to remember that software engineering has no silver bullets; hence, each decision depends on the system and requirements.

More reasons why reliable messaging is so important

Distributed Transactions using the Two-Phase Commit Protocol (2PC) is not an option for microservice-based applications. It restricts our options for Databases, Message Buses, etc., as they need to support the protocol explicitly. It can also significantly reduce the availability of our system; for a distributed commit to succeed, all participating components must be online and reachable.

Some business transactions may still need to span across many microservices. Since each microservice has its own private database and Distributed Transactions must be avoided by design, we need a different approach to keep data consistent.

That is where the Saga pattern comes into play. Although the pattern’s details are outside the scope of this post, the important thing to note is that Sagas heavily rely on messaging.

That is one more reason why messaging is so crucial for microservice-based applications, so we need to take extra care that we do it reliably.

Conclusion

Messaging is at the heart of microservice-based application design, so we need to ensure that we do it reliably and predictably.

To that end, there are several solutions we can leverage, depending on the database technology we use and its features, plus several design aspects of our system.

Message/event consumers need to handle events idempotently. The downstream processing needs to ensure that no undesired duplication of effects happens, no matter how often they come across it on the bus. (Many thanks to Ruben Bartelink for contributing this paragraph to the article.)

Finally, when we need to keep data consistent across microservices, we should embrace Eventual Consistency, avoid 2PC and use Sagas instead. The Saga pattern heavily relies on messaging.

Eventual Consistency - Image Source

Want to build expertise in microservices? Check out my complete Collection of Microservices Books and don’t hesitate to drop me a line with your feedback.

Until next time!

Cheers, Tasos.

Become a DrinkBird Insider

Never miss a post! Get the latest articles on tech and leadership delivered to your inbox. Sign Me Up Sent sparingly. Your privacy is a priority. Opt-out anytime.

Recommended Books

Full disclosure: the following are Amazon affiliate links. Using these links to buy books won't cost you more, but it will help me purchase more books. Thank you for your support!