Which technology to pick up next?

Software engineering is a vast, continuously evolving field that one can spend years of learning and practicing before becoming effective and productive. No modern software system is a result of a single technology, but rather of a mixture of different platforms, programming languages, frameworks, libraries, patterns and practices.

Depending on the type and scale of a system, there are different goals to be achieved, and each case is in need of a tailored approach to planning, design, development and quality assurance. Consider the construction analogy: Would you use the same practices to buld a a hospital, a shopping mall, a dog house and a nuclear reactor?

As a software engineer it is vital that you never stop learning, practicing and mastering numerous technologies, so that you can make educated decisions when you are called to design a new system or transform an existing one, to be effective when implementing those decisions, and (equally important) to be able to provide guidance to your team.

That’s a long-term process that practically never stops as long as you keep practicing your craft. It is definitely challenging, exhausting, and can lead to mental burnouts and the feeling of developaralysis. The secret is to pace it, create a backlog with technologies you’re interested in, formulate yearly learning plans, and also having realistic expectations on your progress. Unfortunately, many of us quit trying very soon after picking up a new technology and not being able to produce miracles within a very short time frame.

Success doesn’t happen overnight. Keep your eye on the prize and don’t look back.

– Erin Andrews

The other side of the coin is even more serious. As humans we tend to default to what we already know and reject anything that opposes that knowledge. In other words, we are allergic to change. For a software engineer, this is the quickest path to obsolence. It is vital that we are not just always willing to learn, but also to unlearn.

The most damaging phrase in the language is, “We’ve always done it this way!”

– Grace Hopper

A few technologies from my backlog

As I mentioned above, an efficient way of learning new technologies without being overwhelmed is to create a backlog of technologies you’re interested in and formulate yearly plans. You can also define a number of checkpoints within the year to reevaluate and adjust your plan if necessary, e.g. once every quarter.

This article includes a list of the top technologies from my personal backlog. That means that I have little experience with most of them, but I’ve spend enough time to evaluate them and be able to have a meaningful discussion. Please excuse any inaccuracies and feel free to suggest corrections using the comments section below.

You may notice that some of these technologies are not particularly new, but they have become more relevant than ever. That’s perfectly normal in the software industry, as when a technology matures, others that compliment it become more relevant and oftentimes evolve in parallel.

Functional Programming

Functional programming is not new at all. In fact it can be traced back to 1957 as the first of the three major programming paradigms to be invented (with the other two being Structured and Object Oriented Programming). Functional programs are generally simpler, which makes them easier to write and maintain.

FP helps us avoid a wide range of problems, such as temporal couplings, concurrency issues, and eliminating side effects by imposing discipline on change of state. Why FP has become more important than ever? Here are a few reasons:

- Up until a few years ago, memory was too expensive to make FP practical. Nowadays memory is dirt cheap.

- Modern functional languages use a number of techniques to manage resources more efficiently, e.g. tail call optimization.

- Overall, functional code is more succinct than in other paradigms. In other words, we can achieve more with less code, which makes us more productive and also eases the pain of managing large code bases.

- FP compliments a number of modern technologies, such as Cloud Computing, Microservices and Event Sourcing.

- Most importantly, functional programs are scalable in nature. In general, they don’t rely on mutating variables so they don’t have to protect some “shared state”. When side effects are not an issue, implementing an algorithm across different cores/processors/machines is much, much easier. Let’s see how hardware evolution makes this point even more important.

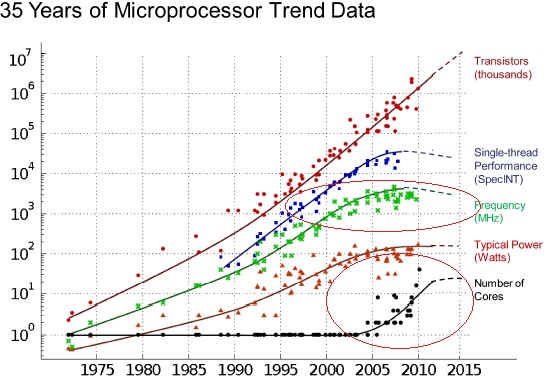

For a few decades hardware engineers were able to steadily increase the throughput of computer systems by pushing CPU clock rates to higher limits, and that worked quite well until something interesting happened. Take a look at the following chart by nap.edu:

It seems that about ten years ago, harware engineers hit a wall on processor speeds, mostly due to physical limitations of the materials the chips are made of. They couldn’t keep increasing throughput with clock rate anymore, so they started multiplying the number of cores per CPU, which means that throughput goes up only if we can take advantage of those cores.

That’s a major challenge for programmers, as we are -in general- extremely inefficient in writing multithreaded code, and that’s exactly why functional languages have suddenly become so popular, even though some of them are quite old. Some of the most used ones in the industry are:

I strongly encourage you to study about the basic concepts of functional programming and learn at least one functional language, even if you don’t intend on using it on your day job. You will soon find out that you can apply numerous functional principles to your standard OOP code, and end up with a much cleaner and much more maintainable code base.

Reactive Programming

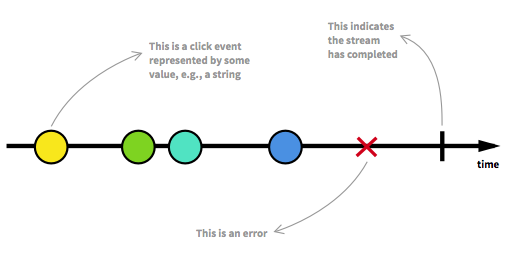

Reactive programming is programming with asynchronous data streams. In a gist, you have the ability to create data streams of anything, such as user inputs, caches and data structures, and then you can listen to those streams and act appropriately.

Furthermore, you have an extensive set of tools and functions to manipulate those streams. If you are already familiar with functional programming you will feel right at home. You can use one or multiple streams as an input to another data stream, and perform purely functional operations such as mapping, merging and filtering.

Reactive Extensions is a feture-rich, battle-tested API for doing reactive programming. It’s used for both server-side and client-side applications and it’s implemented accross a wide variety of programming languages, platforms and frameworks. It’s so reliable that Google has decided to use the JavaScript flavor of Reactive Extensions, aka RxJS, as a core dependency of Angular.

You can find much more information about reactive programming in an excellent post by André Staltz, from which I’ve also taken the image above.

Microservices

In 2006, Werner Vogels (Amazon’s CTO) gave a presentation at the JAOO conference, where he dicussed -among other things- how small teams build and run services that have their own databases. Fast forward in the future, this structure is now known as DevOps, and the underlying architecture is known as microservices.

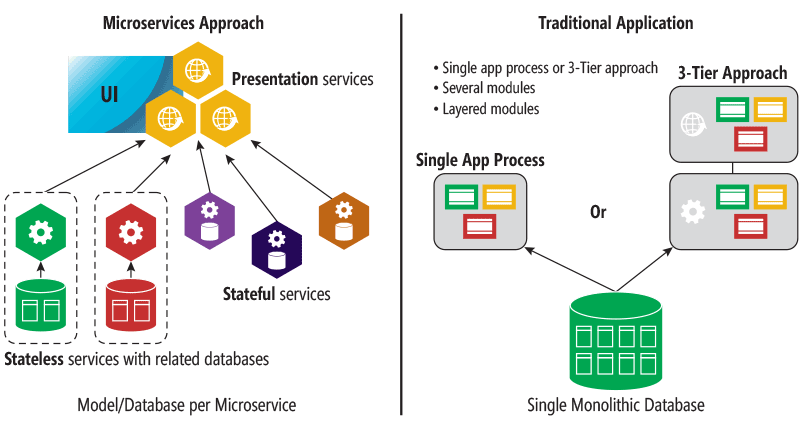

Microservices is an emerging paradigm of software modularization. In summary, microservices are the result of applying the Single Responsibility Principle at a service level.

Instead of developing and deploying an application as a single piece (referred to as a monolith in bibliography), we build it as a number of feature-focused services that communicate over a network. There are numerous benefits associated with this approach.

Each microservice has its own data storage, can be deployed / upgraded / replaced / scaled independently from the rest, and and can also be implemented in different technologies (platforms / programming languages) from the rest. These small pieces of functionality end up formulating the end application.

image taken from microsoft.com

image taken from microsoft.com

Most importantly, work can be distributed accross teams more efficiently, since each microservice includes a full vertical slice of the application. That way dependencies between teams are minimized, development is faster, and practices such as continuous delivery and blue-green deployment become much more possible.

Of course the organization adopting the microservices approach has to adapt its structure accordingly, since teams have to organize around business capabilities and not different application tiers or technologies. Furthermore, the organization has to adopt the DevOps mindset and invest on infrastructure automation, as managing all those moving parts manually is proven to be not such a good idea.

There is also a wide number of patterns and practices that play really well in microservice-driven scenarios. Next, I’ll describe a few of them.

1. Domain Driven Design (DDD)

This architectural approach was first introduced by Eric Evans in his homonymous book, and its all about making the business domain our number one priority. We consider it to be the heart of the application, so everything is build from the domain model out.

In general, we’re looking to create models that map well to a problem domain. Everything else, such as persistence layers, user interfaces or messaging between the different parts of the application are considered to be details and the decisions around them can be deferred for much later.

It’s the problem domain that needs to be understood, because that’s the magic sauce in the system being built that differentiates your organization’s business from its competitors. If that’s not the case, it’s probably better to abandon the project and use some off-the-shelf product instead.

If you’re going to apply DDD outside of a microservice architecture, then start by reading Domain Driven Design, by Eric Evans . If on the other hand you plan to use it in a microservice driven architecture, you can skip Eric Evans’s book and read Building Microservices: Designing Fine-Grained Systems, by Sam Newman (Amazon affiliate link) directly.

2. Command and Query Responsibility Segragation (CQRS)

This pattern was first described by Greg Young. In a nutshell, we separate operations that read data from those that update data by using different interfaces. It is primarily used to increase scalability, maximize performance, improve security, and overall make systems more flexible.

This separation can be valuable for a number of situations, especially in a microservice-driven architecture, but we also need to beware of the extra complexity this pattern brings along.

You can read more about CQRS at microsoft.com.

3. Event Sourcing

Event Sourcing is an alternative way of storing application data. Typically, we have a store of mutable data and we perform the standard CRUD operations to fulfill the needs of the application. In such scenarios, when we edit a record the old values are overwritten and when we delete a record the data is gone forever.

In Event Sourcing we follow a different approach. We use an append-only store to record every single event that describes actions taken on data in specific domains of the application. As a result, an event-sourced system can be deterministically brought back to a state at any point in time, by simply replaying the stream of events logged in the append-only store.

As a programmer you should already be familiar with that strategy, since it’s exactly how GIT works. When we commit code, we only commit the changes since the previous commit. A revision then is a fixed point in history. When we check out a revision, GIT just replays all commits (events) that happened between the active revision and the targeted one.

It’s by no means a new concept. Numerous industries have been using it for hundreds of years, such as finance, accounting, insurance, medical and legal. Doctor’s won’t erase your medical history when they get new information, as like banks won’t determine your available funds based on a database column.

Event sourcing brings numerous other benefits to the table. Apart from providing a complete audit history, it can also provide data consistency and improve performance, scalability and responsiveness. Finally, as mentioned in confluent’s blog:

Event sourcing enables building a forward-compatible application architecture — the ability to add more applications in the future that need to process the same event but create a different materialized view.

Wrapping up, there are a few more things that need to be mentioned:

- CQRS and Event Sourcing are usually mentioned together. Although neither one is a prerequisite for the other, they complement each other really nicely.

- Event Sourcing is functional by nature. In FP terms, the current application state is a left fold of previous behaviors, a snapshot is a memoization of the fold, and a projection is a fold over your event log.

- You don’t need to apply Event Sourcing to your whole system. You can instead pick specific domains of the application where ES makes sense, and apply it just there.

- Two excellent tools to use in Event Sourcing scenarios are Greg Young’s Event Store and Apache Kafka. Kafka is actually not specific to Event Sourcing, and can be leveraged in a wide range of scenarios.

You can read more about Event Sourcing at microsoft.com.

Conclusion

There is always something new to learn, and as a software professional you should never stop learning and evolving. I hope this post gave you a few ideas on what to study next, as well as a number of useful sources for further reading.

Feel free to use the comment section below and tell me about the top technologies from your backlog, or suggest corrections to any inconsistencies you’ve come accross in the article. Most importantly, have fun learning!

Become a DrinkBird Insider

Never miss a post! Get the latest articles on tech and leadership delivered to your inbox. Sign Me Up Sent sparingly. Your privacy is a priority. Opt-out anytime.

Recommended Books

Full disclosure: the following are Amazon affiliate links. Using these links to buy books won't cost you more, but it will help me purchase more books. Thank you for your support!